Robotic retina offers second chance for sight

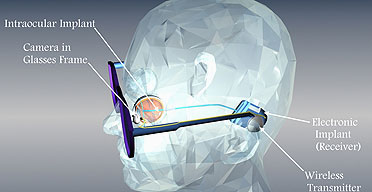

[FONT=Geneva,Arial,sans-serif]How the retinal implant works. Photograph: University of Southern California

[/FONT]

Six blind patients have had their sight partially restored by a "bionic eye" surgically implanted onto their retina. Although it restores only very rudimentary vision, the device has proved so successful that its developers are about to begin a study of a more sophisticated version on between 50 and 75 patients.

If this trial goes to plan, the device could be available to patients in two years and one day it could be used to digitally enhance human sight.

The bionic eye works by converting images from a tiny camera mounted on a pair of glasses into a grid of 16 electrical signals that transmit directly to the nerve endings in the retina.

"It's amazing that even with 16 pixels how much our subjects have been able to do," said Professor Mark Humayun at the Doheny Eye Institute at the University of Southern California who has pioneered the device.

"We were completely wrong...We thought from simulations that 16 would only give you distinction between light and dark and maybe some grey scale."

In fact, subjects are able to tell the difference between objects such as a cup, a plate and a knife. They can also tell which direction objects are moving in front of them. "The brain is able to fill in a lot of the information," he added.

One of Prof Humayun's patients is Terry Byland, 58, from Corona, near Los Angeles. He used to sell power tools before going blind from a condition called retinitis pigmentosa in 1993.

"At the beginning, it was like seeing assembled dots - now it's much more than that," he said. His field of view is about 30cm wide, but it allows him to cross a busy street and see white lines on the road.

"When I am walking along the street I can avoid low hanging branches - I can see the edges of the branches, so I can avoid them," he added.

And it has had a profound impact on his life. "I was with my son, walking, the first time - it was the first time I had seen him since he was five years old. I don't mind saying, there were a few tears wept that day."

The camera in the glasses sends a wireless signal to a pocket device the size of a blackberry, which processes the images in real time into a four by four grid of electrical signals. This grid is then transmitted wirelessly to the eye implant, which converts these into signals sent directly to nerve endings in the retina.

In the current devices the receiver for the signal is implanted under the skin behind the ear with a wire connection to the eye implant, but the team have shrunk the electronics so the improved version fits under the skin around the eye.

More significantly, it now has 60 pixels instead of 16 and because it is smaller the operation to implant it is much less traumatic, taking just 90 minutes instead of eight hours. Prof Humayun predicts that it will cost around $30,000 (£15,400).

All of the image processing happens instantaneously. "It has to be real time because if it isn't and you move your head and the screen is delayed...you start to feel sick and dizzy. I'm sure you've experienced that in movie theatres," said Prof Humayun.

Developing the first device took 16 years of research, but the 60 pixel version has taken just four. The implant is not suitable for every form of blindness. If the optic nerve or vision processing centres in the brain are damaged it cannot help, but there are many conditions in which patients lose the function of the receptor cells in the retina and go blind, even though the neural circuitry behind is intact.

Age-related macular degeneration, for example, is a common condition in which patients gradually lose sight in the centre of their field of vision. It affects 15% of people aged 75 or over.

Prof Humayun believes his implants will be most successful in patients who were once fully sighted rather than people who were blind from birth. However he wants to try the device out in those people too.

"I think the jury's still out," he said, "I don't think it will be as effective as somebody who had vision into their 20s, 30s and 40s, but it is definitely a population we would like to try."

Stevie Wonder is one of his patients who has expressed an interest in the technology, but as someone who lost his sight very early in life, he will not be one of the initial trial patients. "He is very much for really raising awareness of the technology so that people can get to hear about it and really understand it."

Prof Humayun predicts that future versions of the bionic eye would need at least 1000 pixels for patients to recognise faces. And even further off is the possibility of manipulating the images the patients sees, for example allowing them to pause or enhance it by zooming in.

'I see faces as shadows'

"The last thing you want to hear is that you are going blind - and that there's nothing they can do." That was the nightmare that faced Terry Byland from Corona near Los Angeles in 1985.

By 1993 a rare condition called retinitis pimentosa, that affects around 1 in 3500 people had robbed him of his sight. But 13 years later Prof Humayun accepted him as the sixth patient to trial his experimental bionic eye.

After the 8 hour operation to put it in place, the first he saw was a sequence of specks of light as the experimenters tested the device.

"It was amazing to see something," he said, "We were told before it would be a very slow and very tedious process. Well we've gone far beyond that. It's such an exciting project to be a part of."

The device has helped him to regain his independence. "My visual cortex, which was dormant, is learning to work again. When I'm in my home, or another person's house, I can go into any room and switch the light on, or see the light coming in through the window." "It is going from a good guess to knowing what I see. I can't recognise faces but I can see them like a dark shadow. I can cross a busy street - I can see white lines on the crosswalk."

James Randerson, science correspondent,

in San Francisco

Guardian Unlimited

© Guardian News and Media Limited 2007

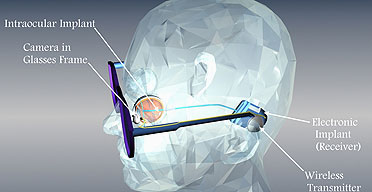

[FONT=Geneva,Arial,sans-serif]How the retinal implant works. Photograph: University of Southern California

[/FONT]

Six blind patients have had their sight partially restored by a "bionic eye" surgically implanted onto their retina. Although it restores only very rudimentary vision, the device has proved so successful that its developers are about to begin a study of a more sophisticated version on between 50 and 75 patients.

If this trial goes to plan, the device could be available to patients in two years and one day it could be used to digitally enhance human sight.

The bionic eye works by converting images from a tiny camera mounted on a pair of glasses into a grid of 16 electrical signals that transmit directly to the nerve endings in the retina.

"It's amazing that even with 16 pixels how much our subjects have been able to do," said Professor Mark Humayun at the Doheny Eye Institute at the University of Southern California who has pioneered the device.

"We were completely wrong...We thought from simulations that 16 would only give you distinction between light and dark and maybe some grey scale."

In fact, subjects are able to tell the difference between objects such as a cup, a plate and a knife. They can also tell which direction objects are moving in front of them. "The brain is able to fill in a lot of the information," he added.

One of Prof Humayun's patients is Terry Byland, 58, from Corona, near Los Angeles. He used to sell power tools before going blind from a condition called retinitis pigmentosa in 1993.

"At the beginning, it was like seeing assembled dots - now it's much more than that," he said. His field of view is about 30cm wide, but it allows him to cross a busy street and see white lines on the road.

"When I am walking along the street I can avoid low hanging branches - I can see the edges of the branches, so I can avoid them," he added.

And it has had a profound impact on his life. "I was with my son, walking, the first time - it was the first time I had seen him since he was five years old. I don't mind saying, there were a few tears wept that day."

The camera in the glasses sends a wireless signal to a pocket device the size of a blackberry, which processes the images in real time into a four by four grid of electrical signals. This grid is then transmitted wirelessly to the eye implant, which converts these into signals sent directly to nerve endings in the retina.

In the current devices the receiver for the signal is implanted under the skin behind the ear with a wire connection to the eye implant, but the team have shrunk the electronics so the improved version fits under the skin around the eye.

More significantly, it now has 60 pixels instead of 16 and because it is smaller the operation to implant it is much less traumatic, taking just 90 minutes instead of eight hours. Prof Humayun predicts that it will cost around $30,000 (£15,400).

All of the image processing happens instantaneously. "It has to be real time because if it isn't and you move your head and the screen is delayed...you start to feel sick and dizzy. I'm sure you've experienced that in movie theatres," said Prof Humayun.

Developing the first device took 16 years of research, but the 60 pixel version has taken just four. The implant is not suitable for every form of blindness. If the optic nerve or vision processing centres in the brain are damaged it cannot help, but there are many conditions in which patients lose the function of the receptor cells in the retina and go blind, even though the neural circuitry behind is intact.

Age-related macular degeneration, for example, is a common condition in which patients gradually lose sight in the centre of their field of vision. It affects 15% of people aged 75 or over.

Prof Humayun believes his implants will be most successful in patients who were once fully sighted rather than people who were blind from birth. However he wants to try the device out in those people too.

"I think the jury's still out," he said, "I don't think it will be as effective as somebody who had vision into their 20s, 30s and 40s, but it is definitely a population we would like to try."

Stevie Wonder is one of his patients who has expressed an interest in the technology, but as someone who lost his sight very early in life, he will not be one of the initial trial patients. "He is very much for really raising awareness of the technology so that people can get to hear about it and really understand it."

Prof Humayun predicts that future versions of the bionic eye would need at least 1000 pixels for patients to recognise faces. And even further off is the possibility of manipulating the images the patients sees, for example allowing them to pause or enhance it by zooming in.

'I see faces as shadows'

"The last thing you want to hear is that you are going blind - and that there's nothing they can do." That was the nightmare that faced Terry Byland from Corona near Los Angeles in 1985.

By 1993 a rare condition called retinitis pimentosa, that affects around 1 in 3500 people had robbed him of his sight. But 13 years later Prof Humayun accepted him as the sixth patient to trial his experimental bionic eye.

After the 8 hour operation to put it in place, the first he saw was a sequence of specks of light as the experimenters tested the device.

"It was amazing to see something," he said, "We were told before it would be a very slow and very tedious process. Well we've gone far beyond that. It's such an exciting project to be a part of."

The device has helped him to regain his independence. "My visual cortex, which was dormant, is learning to work again. When I'm in my home, or another person's house, I can go into any room and switch the light on, or see the light coming in through the window." "It is going from a good guess to knowing what I see. I can't recognise faces but I can see them like a dark shadow. I can cross a busy street - I can see white lines on the crosswalk."

James Randerson, science correspondent,

in San Francisco

Guardian Unlimited

© Guardian News and Media Limited 2007