totalgenius

Inactive User

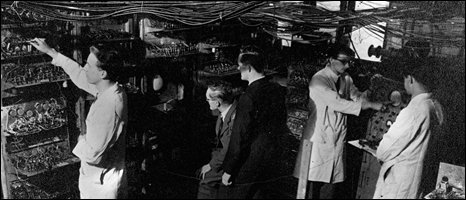

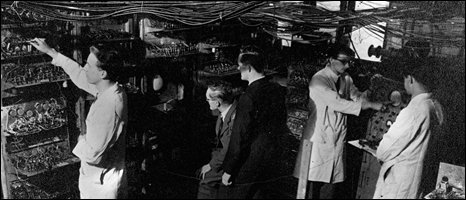

Sixty years ago the "modern computer" was born in a lab in Manchester.

The Small Scale Experimental Machine, or "Baby", was the first to contain memory which could store a program.

The room-sized computer's ability to carry out different tasks - without having to be rebuilt - has led some to describe it as the "first modern PC".

Using just 128 bytes of memory, it successfully ran its first set of instructions - to determine the highest factor of a number - on 21 June 1948.

"We were extremely excited," Geoff Tootill, one of the builders of Baby told BBC News.

"We congratulated each other and then went and had lunch in the canteen."

Mr Tootill, and three other surviving members of the Baby team, will be honoured by the University and the British Computer Society at a ceremony in Manchester.

Number cruncher

Baby was the successor to machines such as the American ENIAC and the UK's Colossus.

ENIAC was built to calculate the trajectory of shells for the US army, whilst Colossus was used to decrypt messages from the German High Command during World War II.

Both computers were able to be reprogrammed but this could involve days of rewiring. Baby was designed to overcome this limitation.

"It was the earliest machine that was a computer, in the sense of what everyone today understands a computer to be," explained Chris Burton of the Computer Conservation Society (CCS).

"It was a single piece of hardware which could perform any application depending on what program you put in."

The key to this ability was its memory, built from a cathode ray tube (CRT), which could be used to store a program.

"It was an extraordinary analogue for today's DRAM (dynamic random access memory)," said Mr Burton.

Electrical charges on the screen of the CRT were used to represent binary information. A positive charge represented a one and a negative charge a zero.

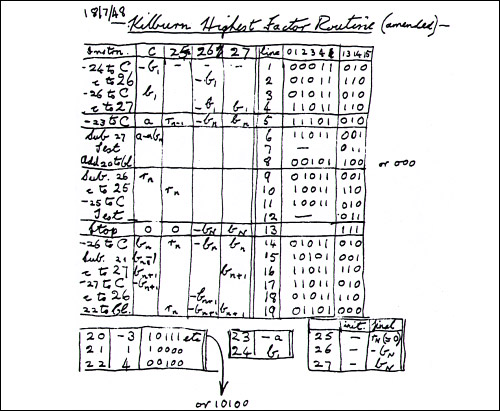

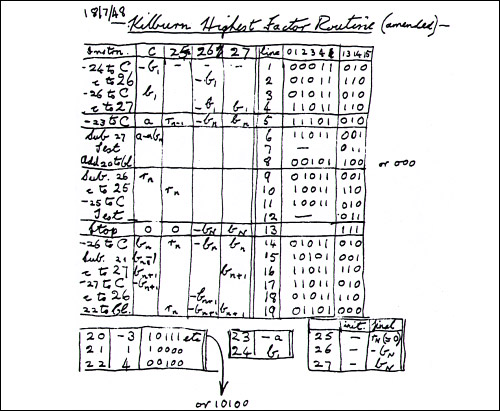

A page from Geoff Tootill's notebook shows a program written for Baby. All the data and programs had to be written in 1024 bits.

A metal grid attached to the screen read the different charges. A graphical representation - dashes for a one and dots for a zero - was displayed on a second CRT wired in parallel to the memory device.

"The operator peered at the monitor tube and he could see the same patterns as in the storage tube," said Mr Burton.

The memory gave programmers a total of 1024 bits, or 128 bytes, to play with. This had to store both the program and all of the data to be crunched.

By comparison, a modern 1GB DRAM chip can store around 8 billion bits.

Dashing times

However, the size of the memory did not prevent the Manchester University team writing relatively complex programs.

"You can write very sophisticated and interesting programs even with that limitation," said Mr Burton.

"They're not efficient, but nobody was talking about efficiency it was about feasibility."

The first program was written by the late Tom Kilburn to work out the highest factor of a prime number.

"We used this, of course, to test the machine," said Mr Tootill.

"It took it a very long time so we had our leisure to see how the circuits were working - to see if any were on the verge of failure that sort of thing."

Because of the limitations of the display the team tested the machine using prime numbers.

"If you give it a prime number to try then the highest factor of that is one," said Mr Burton.

"If what they saw when they ran the program was a one - in other words a dash when everything else was dots - then bingo they knew it was working."

The team eventually refined their techniques, writing more complex programs and adding to the computers memory.

Baby morphed into the Manchester Mark I and eventually the first commercial general purpose computer, the Ferranti Mark I.

"It really must have been an extraordinary, exciting and heady time," said Mr Burton.

A working replica of Baby is on display at the Museum of Science and Industry in Manchester.

By Jonathan Fildes

http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/technology/7465115.stm

The Small Scale Experimental Machine, or "Baby", was the first to contain memory which could store a program.

The room-sized computer's ability to carry out different tasks - without having to be rebuilt - has led some to describe it as the "first modern PC".

Using just 128 bytes of memory, it successfully ran its first set of instructions - to determine the highest factor of a number - on 21 June 1948.

"We were extremely excited," Geoff Tootill, one of the builders of Baby told BBC News.

"We congratulated each other and then went and had lunch in the canteen."

Mr Tootill, and three other surviving members of the Baby team, will be honoured by the University and the British Computer Society at a ceremony in Manchester.

Number cruncher

Baby was the successor to machines such as the American ENIAC and the UK's Colossus.

ENIAC was built to calculate the trajectory of shells for the US army, whilst Colossus was used to decrypt messages from the German High Command during World War II.

Both computers were able to be reprogrammed but this could involve days of rewiring. Baby was designed to overcome this limitation.

"It was the earliest machine that was a computer, in the sense of what everyone today understands a computer to be," explained Chris Burton of the Computer Conservation Society (CCS).

"It was a single piece of hardware which could perform any application depending on what program you put in."

The key to this ability was its memory, built from a cathode ray tube (CRT), which could be used to store a program.

"It was an extraordinary analogue for today's DRAM (dynamic random access memory)," said Mr Burton.

Electrical charges on the screen of the CRT were used to represent binary information. A positive charge represented a one and a negative charge a zero.

A page from Geoff Tootill's notebook shows a program written for Baby. All the data and programs had to be written in 1024 bits.

A metal grid attached to the screen read the different charges. A graphical representation - dashes for a one and dots for a zero - was displayed on a second CRT wired in parallel to the memory device.

"The operator peered at the monitor tube and he could see the same patterns as in the storage tube," said Mr Burton.

The memory gave programmers a total of 1024 bits, or 128 bytes, to play with. This had to store both the program and all of the data to be crunched.

By comparison, a modern 1GB DRAM chip can store around 8 billion bits.

Dashing times

However, the size of the memory did not prevent the Manchester University team writing relatively complex programs.

"You can write very sophisticated and interesting programs even with that limitation," said Mr Burton.

"They're not efficient, but nobody was talking about efficiency it was about feasibility."

The first program was written by the late Tom Kilburn to work out the highest factor of a prime number.

"We used this, of course, to test the machine," said Mr Tootill.

"It took it a very long time so we had our leisure to see how the circuits were working - to see if any were on the verge of failure that sort of thing."

Because of the limitations of the display the team tested the machine using prime numbers.

"If you give it a prime number to try then the highest factor of that is one," said Mr Burton.

"If what they saw when they ran the program was a one - in other words a dash when everything else was dots - then bingo they knew it was working."

The team eventually refined their techniques, writing more complex programs and adding to the computers memory.

Baby morphed into the Manchester Mark I and eventually the first commercial general purpose computer, the Ferranti Mark I.

"It really must have been an extraordinary, exciting and heady time," said Mr Burton.

A working replica of Baby is on display at the Museum of Science and Industry in Manchester.

By Jonathan Fildes

http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/technology/7465115.stm